It happened in a grad leadership circle, but it could have been an intense exchange at my kitchen table, over green tea or a glass of wine. Everybody spoke at once, so we heard the last student’s sentence overlap with the next person’s question. Then suddenly our roundtable session fell silent for what seemed like minutes when Mohammed, a Palestinian, and Hahn, an Israeli, heated up our debate.

It happened in a grad leadership circle, but it could have been an intense exchange at my kitchen table, over green tea or a glass of wine. Everybody spoke at once, so we heard the last student’s sentence overlap with the next person’s question. Then suddenly our roundtable session fell silent for what seemed like minutes when Mohammed, a Palestinian, and Hahn, an Israeli, heated up our debate.

We’d told stories of leaders who lose employees to drugs, and employees who lose their cool over conflicts. So their interjection of middle-east peace possibilities didn’t seem tied into reality, much less our conversation.

“Ok, it’s nothing but chaos,” Hahn said as he held up his iPad and refreshed the screen to show a new protest in Gaza. “But that’s cause nobody’s ready to risk…”

“Risk what?” Mohammed asked.

“Imagine the peace we’d cultivate in the middle-east if just one Israeli leader acted through one Palestinian’s viewpoint, Mohammed said. And he added, … “and picture one Palestinian responding through an Israeli’s perspective.”

Silence again. You could almost taste the tension in the room.

“But think of the huge risk that would take,” a student suggested. Several others agreed that such a risk would be enormous in the current climate where people reach for chemical fixes before conflict resolutions.

“So where’d a person begin?” I asked, hoping to see what grad students think it would take to turn their own rough tides toward calmer shores. “What risks do you cultivate … if any?”

The notion of empathy suddenly came up and Margaret said her granddad’s favorite saying was, “Risk speaking to every human as if that person was wounded.”

The group gradually concluded that the right risk could turn a tide for yourself or somebody you know. And you don’t always have to move a mountain, or erase the entire opioid crisis at the same time.

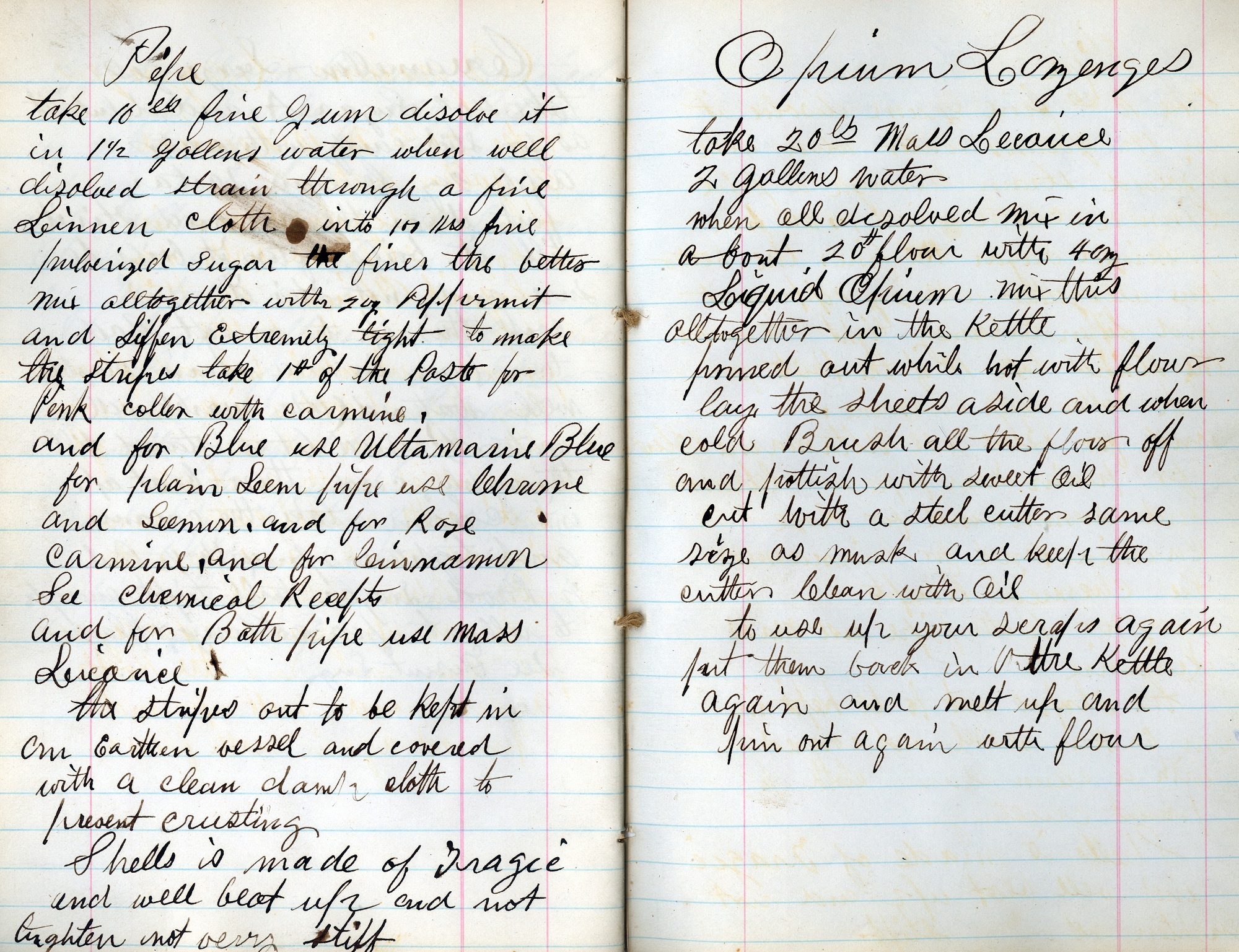

Even in our current drug epidemic, where researcher Dr. Tara Gomes in Toronto, warns us that opioids account for one in five US deaths of those aged 25 to 34, grads insisted that one risk can turn the tide in a drug user’s favor.

I couldn’t help wondering, what if we looked at life through a depressed friend’s eyes? Or a lonely peer’s perspective?

A lifetime of brain research taught me that our brains both rejuvenate and refuel for risks and rewards with natural drugs such as dopamine. Stockpile dopamine by taking smaller risks on ordinary days, and it prepares you for a mental makeover when bigger challenges loom up. Dopamine needed, for example, to sky-dive may be far more than any risk-potion required to pull-off a belly-flop into your backyard swimming pool.

It’s clear that my grad students want more than survival in our current climate of emotional slumps, drug overdoses and increasing suicides. They accept that it depends on an ability to risk new approaches. They seem ready to reboot human possibilities rather than stall over social shortcomings.

They even spoke of starting small. “Even a walk along a new path to work builds more do-it-different-power,” one said.

“Sure, but how do you help older employees who refuse to try anything new?” one student asked. Heads nodded.

“They criticize technology and won’t try to help us improve the boring routines that hold us all back,” another student complained.

I pulled up a research survey that supported the grads’ grumbles. When asked what one thing they regretted most in their lives, a group of senior citizens listed, above any other: “I regret the fact that I didn’t take more risks.”

The survey kindled a new discussion. How can two generations look to the future and support risks to progress together?

It may start by repairing a broken relationship at work so that both generations gain a new boost of confidence! Eleanor Roosevelt put it this way: “No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.” She also said: “You have to accept whatever comes and the only important thing is that you meet it with the best you have to give.”

Before long the grads moved from stomping on seniors’ comfort zones to explaining the risks Madeleine L’Engle had in mind when she said: “The great thing about getting older is that you don’t lose all the other ages you’ve been.” Through reflection they began to hedge their bets, and reach together for better odds that they could make a difference.

“We have to reflect if we’re to risk and adjust,” one gal from the English department said. “I like to listen to music – go for a walk – read, or talk to a close friend,” another added.

One student referred us back to the regrets from seniors. “What if we took a minute at the next staff meeting to “write one sentence you’d enjoy posted on your gravestone”?

They discussed how to encourage workers to take one step toward making that gravestone dream a reality at work today.

As students clothed fantasy into facts and facts in fantasy, they plotted for ways to help older workers risk want to come on board.

“We could journal our feelings to get into sync so peers and seniors begin to bridge generational differences,” Margo suggested.

“Listen more? Ask co-workers to help fix a broken thing at work?” Mark added. They discussed people that elicit thanks they might show to a peer or boss.

To capitalize on others’ talents is to step out, they agreed to step up and use more of their own potential, even take risks if older workers failed to recognize or use their potential.

That suggestion brought the grads back down to earth like an air balloon without air. “Unfortunately, most established leaders where I work block renewal of any kind,” Mark said. Steph jumped in to agree. “Comforts of tenure and secure leadership positions take precedence over risk-taking or learning from one another.”

That suggestion brought the grads back down to earth like an air balloon without air. “Unfortunately, most established leaders where I work block renewal of any kind,” Mark said. Steph jumped in to agree. “Comforts of tenure and secure leadership positions take precedence over risk-taking or learning from one another.”

I shared how I’d addressed leaders at an international conference the week earlier, on the topic of brain based risks for renewal. After my first talk, a young CEO asked, “Why do older leaders at work criticize or kill every innovation introduced?” That question bothered me during my entire time overseas, partly because I’d heard similar laments from graduates, and partly because I’m “older myself.”

On the trip back, I discussed this with fellow leaders, and listened for cynicism. We spoke of enormously broken systems as well as a desire from many for the freedom to change. A desire to take risks to fuel that needed change, though? Not so much.

“Intimidation plays a bigger role than we realize,” I suggested to grads.

Look at how many people feel threatened by new ideas about brains. Some worry about watered down knowledge when we learn interactively, and then try to battle paradigms embraced by a system stuck in outmoded lectures.

One grad said, “It’s equal to mending methods of slavery, in past.”

Another student came back with, “Just as we had to rid society of slavery, we need to abolish stale systems before we can create changes based on how human minds operate.”

They concluded that without opportunity or motivation to cultivate a taste for risks and innovation, we create cynicism from roots upward.

As I thought about my recent leadership conference, I challenged the grads again, “Ever heard any stories of older masters of their trades? Folks who let go of traditional turf for fresh renewal rivers that splash new life?”

Concerns were raised about walking the talk, “We preach renewal theory, but then support outmoded leaders only,” one grad said. Others jumped in, Excuses ranged from, “Renewal doesn’t fit,” to “There isn’t enough time.” In response, one person asked, “Time for what?” It became clear that to carry on as usual looked like time spent efficiently, where many of them worked.

No wonder research shows that very few people enjoy what they do all day at work.

“So why can’t social structures embrace new insights the way medicine experiences change with every new breakthrough in science?” I asked them

“Not every brain breakthrough arrives fully developed,” one scientist argued. “Let’s build on what we know and test new hypothesis together,” another suggested.

Discussions heated at times, but we typically came back again and again to the key question, “How can risk-taking cultivate more curiosity and build better possibilities?”

Renewed ideas crisscross our tables with risks much like mechanics take to adjust airplanes before each new successful flight.

The graduate students agreed that when a full range of intelligences is welcomed in any community, “harmony begins to replace exclusion and discrimination.” It made sense in our discussion, but they saw it as less possible where they worked.

“Sure, people find contentment when they use intellectual gifts and capabilities to conquer challenges they face,” Pete said. “But at work we often do whatever leads to acceptance from others. “

“The opposite is also true,” I pointed out as one gifted writer and teacher, Maya Angelou risked speaking up for change.

Angelou’s friends often tell you that she spoke up without fear whenever racial or sexist slurs slink into her circles. On several occasions Maya asked prominent people to leave her home abruptly, because in conversation they subtly slammed somebody else’s culture. Can you imagine asking an invited guest who arrived for the weekend to leave your home, as other guests unpack for the night? In front of an entire circle of celebrity friends? It makes me wonder where people like Maya find passion and purpose to slice silence and diffuse discord. If honest, many of us have endured subtle slurs to other cultures with silent complicity if not with sanction for racism and sexism expressed as jokes. New lyrics for harmony hummed by a few in my lifetime provide melodies that prevent cruel crashes some cultures feel on a regular basis. As I have come to know Maya through her many books, I grew acquainted with a woman not only scarred by vicious slights and slurs, but also met a model scholar with rare sensibility to risk for all humanity.

“No wonder so many applaud her life and work,” one student said. “And she was old too.” He then told us another story to drive home his point.

To cultivate possibilities for harmony does not require the same risk from everybody. Yet risks that lead to excellence and renewal melds humans together in benefits for more than any one age group.

And when either equity or excellence is sacrificed, unity calls for shattered silences the way Maya spoke out even when it means risk to her reputation. In contrast, slavery slithered into even faith filled hearts through history. If we confront our grim reality today we trace its oppression. Light over darkness takes courage to pierce seething silences of discrimination. Broken societies still scream from ghettos, unheard by many.

A grad student reminded us of words in “Sounds of Silence,” where Paul Simon expressed shock over John F. Kennedy’s death in 1964. Still today we talk without speaking, hear without listening, share small-minded jokes that seal lids on oppression of people steeped in silent bloodbaths of discrimination. Rather than risk shared journeys across cultures we stumble and stall in our own nemesis, again and again.

People like Angelou, traded popularity for silence shattered, and paid high fees for freedom. Nelson Mandela sat in prison a good part of his life to risk breaking a silence that slaughtered people like Martin Luther King and that still adds its stench today. Name after name came up of those who crossed over differences and risked cultivating peace.

As our roundtable ended, Hahn shared how Mark Mathabane escaped South African ghettos, by looking at possibilities through a wider lens. From his book, Kaffir Boy in America, Mark’s healing words challenged our group to risk speaking to one person in the coming week, as if that person was wounded. We fully expected to turn a tide or two by addressing a broken situation through another’s eyes.

About the author: Ellen Weber

Dr. Ellen Weber teaches a grad leadership class called, Lead Innovation with the Brain in Mind, in a New York MBA program. The author of several brain based books, Ellen recently retired from international work with leaders who wish t use more mental potential. She now hopes to inspire others through creative non-fiction, to live, learn and lead by unleashing newly discovered neural benefits into their efforts. Connect with Ellen through social media at Brain Leaders and Learners Blog, Mita Brain Center Facebook, Pinterest, Twitter, Instagram, Google+, and on LinkedIn.

recipes and memories of all the past seasons.

recipes and memories of all the past seasons. headed off to their mom, others shared with friends or neighbors.

headed off to their mom, others shared with friends or neighbors.

After a long career in public broadcasting, Jeanie Croope is now doing all the things she loves — art, photography, writing, cooking, reading wonderful books and discovering a multitude of new creative passions. You can find her blogging about life and all the things she loves at The Marmelade Gypsy.

After a long career in public broadcasting, Jeanie Croope is now doing all the things she loves — art, photography, writing, cooking, reading wonderful books and discovering a multitude of new creative passions. You can find her blogging about life and all the things she loves at The Marmelade Gypsy.

And so, on that early September morning, my mother and I went to London for what would be two weeks of theatre, history and fun.

And so, on that early September morning, my mother and I went to London for what would be two weeks of theatre, history and fun.

traveling for myself and to be with Rick, certainly. But I was also traveling for my mom.

traveling for myself and to be with Rick, certainly. But I was also traveling for my mom. of a very few who actually knew my mom and remembered her.

of a very few who actually knew my mom and remembered her. delectable lunch with one of her old friends.

delectable lunch with one of her old friends.

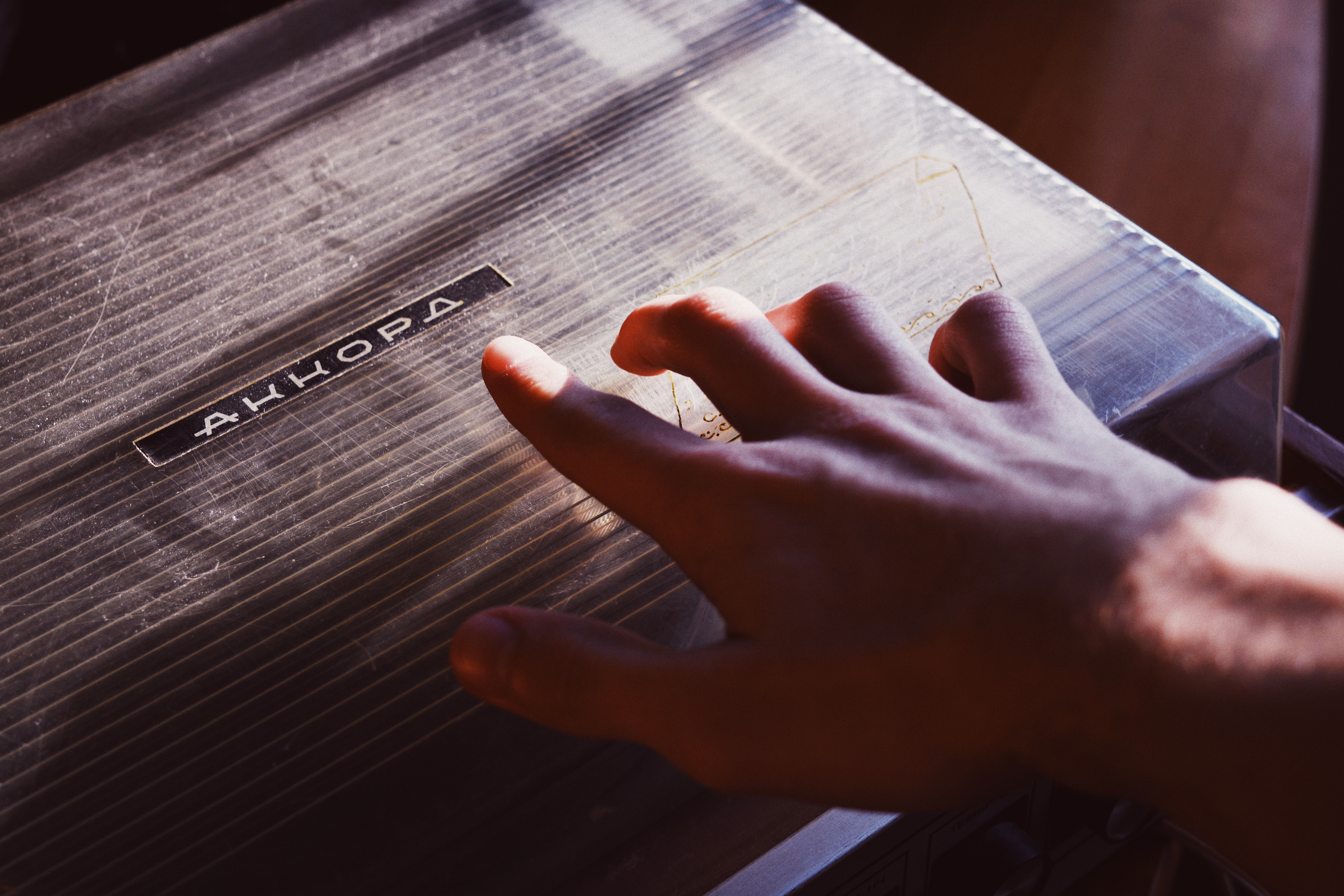

Currently a resident of New Bedford, MA, Fran Hutchinson experienced a “poetic incarnation” while embedded in the 80’s folk scene in Boston. Occupied variously as live calendar producer for WGBH’s Folk Heritage, contributing editor at the Folk Song Society of Greater Boston’s monthly Folk Letter, artist manager and booking agent, and occasional concert producer, she was surrounded by exceptional music and musicians, including those she had long listened to and admired. The result was a rich source of inspiration for verse, of which she took full advantage. No longer writing poetry, Fran has recently been the recipient of a surgically altered back and two new knees, and spends her time reading and listening to music (natch), texting and emailing long-distance friends, and hanging with her posse at the Community center.

Currently a resident of New Bedford, MA, Fran Hutchinson experienced a “poetic incarnation” while embedded in the 80’s folk scene in Boston. Occupied variously as live calendar producer for WGBH’s Folk Heritage, contributing editor at the Folk Song Society of Greater Boston’s monthly Folk Letter, artist manager and booking agent, and occasional concert producer, she was surrounded by exceptional music and musicians, including those she had long listened to and admired. The result was a rich source of inspiration for verse, of which she took full advantage. No longer writing poetry, Fran has recently been the recipient of a surgically altered back and two new knees, and spends her time reading and listening to music (natch), texting and emailing long-distance friends, and hanging with her posse at the Community center.

Season one, or course, is the divorce, what it is like during that.

Season one, or course, is the divorce, what it is like during that. So, how did my mother and I form our mutual Grace and Frankie habit? It all started when she was visiting me: I had her cornered, and so she had to finally watch the show. Much like me, she was hooked just a few episodes in. We binged the entire first season in that week and it was excellent.

So, how did my mother and I form our mutual Grace and Frankie habit? It all started when she was visiting me: I had her cornered, and so she had to finally watch the show. Much like me, she was hooked just a few episodes in. We binged the entire first season in that week and it was excellent.

It happened in a grad leadership circle, but it could have been an intense exchange at my kitchen table, over green tea or a glass of wine. Everybody spoke at once, so we heard the last student’s sentence overlap with the next person’s question. Then suddenly our roundtable session fell silent for what seemed like minutes when Mohammed, a Palestinian, and Hahn, an Israeli, heated up our debate.

It happened in a grad leadership circle, but it could have been an intense exchange at my kitchen table, over green tea or a glass of wine. Everybody spoke at once, so we heard the last student’s sentence overlap with the next person’s question. Then suddenly our roundtable session fell silent for what seemed like minutes when Mohammed, a Palestinian, and Hahn, an Israeli, heated up our debate.

That suggestion brought the grads back down to earth like an air balloon without air. “Unfortunately, most established leaders where I work block renewal of any kind,” Mark said. Steph jumped in to agree. “Comforts of tenure and secure leadership positions take precedence over risk-taking or learning from one another.”

That suggestion brought the grads back down to earth like an air balloon without air. “Unfortunately, most established leaders where I work block renewal of any kind,” Mark said. Steph jumped in to agree. “Comforts of tenure and secure leadership positions take precedence over risk-taking or learning from one another.”