In November, 2008, I had the great pleasure of interviewing one of my favorite celebrity chefs, Mario Batali for All Things Girl. Our phone call was only about twenty minutes long, but he talks even faster than I do (people who know me will be impressed by this), and we covered a lot in a relatively brief time.

We’re re-running this piece today (with a few edits), because it’s one of our favorite pieces, and because all of us on the editorial staff here at Modern Creative Life love to play in our own kitchens, and believe that cooking is just as much a creative pursuit as writing, art, or music.

Enjoy!

First, tell us a bit about yourself: How did you get into food? How does someone from the West Coast end up in New Jersey?

I grew up in Seattle to a half-Italian half-French-Canadian family. We were always into food. Everyone in my entire family: my uncles, my aunts, my cousins, my brother, sister, mom, dad. Everybody I know knew how to cook and was interested in food from the inception of picking something or growing something, picking things wild or harvesting them, or shooting birds or fishing and doing the whole thing.

My grandfather was actually a game guide in British Columbia, and brought home lots of moose and elk and all sorts of weird stuff for us to eat – so it was always part of our lives.

When I was fourteen, my family moved to Madrid, Spain. My dad worked with Boeing, so we had some kind of foreign brat lifestyle over in Madrid, which was delightful. And when it was time to go to college, it would seem to me that it would be easier to get to the east coast than to anywhere else, and I had never been to the east coast, let alone anywhere east of Idaho, for that matter.

Oh, wow. Was there culture shock?

You know what? I fell in love with it immediately. I don’t know that my brother or sister would have been ready for it, but after I spent a year there, my brother came and went to Princeton, just down the street. (I went to Rutgers.) I fell in love with New Jersey. I liked the idea of being close to New York without being in New York at that early age, and I went to school to get a degree in Spanish Theatre of the Golden Age and in finance, or economics.

I did that, but while I was doing it, I worked at a place called “Stuff Yer Face” which is a Stromboli and pizzeria in New Brunswick, and fell in love with the immediacy of a dinner rush and – kind of – my ability to actually react well under pressure and cook very quickly as well as making something delicious, so that’s really the start.

Food was obviously a big part of your family, as you’ve said, and you mentioned growing it as well, which brings me to my next question: The concept of “slow foods” and buying local and eating local is very popular right now. What are your thoughts on that?

Long before it was considered a “carbon footprint massacre” to ship things around the world, I have always been a fan of local produce, and for one reason only – a very selfish reason: it’s easier to make food taste delicious if it hasn’t had to travel very far.

Understanding seasonality is something that is born into Italian people’s mentality, when they’re in Italy. Americans have been able to eat asparagus on Christmas Eve for as long as I’ve been alive, and that’s one of the tragedies of successful commercial farming is that in fact it removes seasonality from things. It also removes the kind of high points that you can get when you eat something that is in season, so I’m all about eating seasonally, eating and buying locally, and supporting farmers whose names you actually know.

And what you’ll capture is: when you’re tasting something in Parma, on a Thursday afternoon in October, and it’s either right in the middle of, or right before or right after the grape harvest and you taste a plate of prosciutto – nothing more, just a simple plate of prosciutto, maybe with some bread on the side – you can smell in the food everything that’s going on around you in the atmosphere. You can smell the way the – kind of – wind smells, and the flavor of the localness, and if you can capture that in whatever part of the country that you’re at, then you have done a great job as a cook, and understanding and working with that kind of local flavor is something that is so unique.

What happened a lot of times in the fancy restaurant world of the last twenty years is that a luxury item became the item that everyone wanted to have, so they had caviar and they had fois gras and they had all this stuff that had really nothing to do with the place that you’re at. What I’m looking for – when I go somewhere traveling, what I’m looking for is something that is geo-specific, something that tastes like it could only be had here, and that – in Texas – could be any kind of barbecue; it could be any kind of crazy onion; it could be any kind of good chili. It could be made by anybody and it doesn’t have to be fancy, but what it has to do is represent that local flavor.

You’ve mentioned living in Spain as a teenager. Did that experience have anything to do with the decision to make your show On the Road Again: Spain [PBS, Fall 2008]?

Yes, well. When I started to talk about the producer – about us doing TV – and he said, “Well how about doing something on Spain which is an undiscovered jewel?”

And I said, “Well, that’s a great idea. I would love to go back to all my old stomping grounds,” and as it turns out, I was at a dinner party and Gwyneth [Paltrow] was at it and we’ve been friends for about ten years and I was talking to everyone at the table about this kind of new show idea that we were working on, and she demanded to be let in, and it was – I thought she was just being polite.

About two months later, when she heard it being talked about again by somebody else, and I wasn’t there, she called me and said – to make sure that I didn’t cut her out – and that kind of worked. So she also spent some time in high school as an exchange student in Talavera de la Reina, I think it was, outside of Madrid.

And so, the whole Spanish thing is to go back and see how it’s changed – I lived there when [Generalissimo] Franco just had died – and to see how it has come a thousand miles and become the forefront of molecular gastronomy, in addition to being still very much its traditional –kind of – old world self was an easy layup for me, and traveling around, I think it looks like we’re having fun, because in fact we are having fun.

Let’s talk more about Spain. What typifies the cuisine of Spain, as opposed to other Latin countries? We in America tend to think of Latin food as primarily Mexican.

I would say that when you talk about European food, it isn’t really Latin. I would say it’s Mediterranean at that point, and that kind of adds a component to it. Clearly like a lot of southern French cooking, like a lot of northern African cooking, and like all Italian cooking, it’s really based on the lipid of choice and olive oil, of course: number one.

So you have that kind of olive culture to it, which is, for a lot of people, something that tastes exotic, but for most people that I know, that’s something that almost says “home.” It says you’re where you should be, and the olive oil being kind of pervasive in all of the dishes, if there’s another flavor that I could put my palate on, there’s almost a smoky component to a lot of the things that they cook, and even some of the things that are raw. And they are not afraid to bring things to the edge of nearly burnt or very dark brown and letting that be kind of the extension of its ultimate caramelization.

And when you taste these things, and even – sometimes the ham and sometimes even the wine, or like a soup, a bean soup – it will have just lightly scorched on the bottom and on purpose. I’d say that there’s something almost smoky to it and whenever anything gets in touch with that magnificent paprika they call pimento, then that also becomes a real kind of intensive part of the flavor – kind of – portfolio.

You mentioned the term molecular gastronomy. Can you explain that a little bit?

Ah, well that is where food preparers, cooks, guys like Ferran Adria (perhaps the most famous member of the molecular gastronomist club) – they choose to provoke people by changing the texture or the appearance of food into something that it never was before while still trying to retain its essential flavor.

So you’ll have caviar that’s made of green apples, and it’ll have that same kind of pop-y texture, and what they’ll use to do that is some form of sea algae that they mix into a liquid and then they add a different kind of algae to the original substance – say, you took a puree of beans and you mix it with this one product and then you drop it into a water solution that has another product and it will sphere-ify the actual item – the whatever-you-dropped-in-there and then it will allow it to be stable for twenty-four to thirty-six hours. So then you’ll make like a little – some kind of a soup, and then you’ll put something that looks like a little glass ball in it, and in fact it tastes like another kind of soup. Or it tastes like salmon. Or it tastes like… whatever.

So they mess around with the basic tenet of very simple products, and yet they don’t – they do it in a way that will make you feel more intellectually stimulated by something that was already very physically stimulating.

And if they get lost it’s – sometimes it’s just like it’s too abstract. You know, there’s something that doesn’t have any connection, and because the food wasn’t very well prepared, or wasn’t very good when they got it raw, it’s wrong, but that doesn’t happen in all of these restaurants. Generally they’re pretty smart about it and it’s very…provocative…to eat in some of these restaurants. And it’s very much fun. But that said, sometimes it loses its way.

Fun seems to be an important element for all really successful chefs. Do you think fun is important?

Above all, fun should be important. And childishness is superior to adult-ness. And there’s a certain whimsical-ness that is what makes really good meals taste really good.

Sometimes you’ll sit down in the fanciest of restaurants and they have removed any of the fun from the experience in the name of creating high art, and that is when, suddenly, it’s no longer interesting to eat.

I like things to be fun. I like them to be unexpected if possible, but most importantly if the cooks are having fun and making things with really good natural products, odds are possibly with you that it will be delicious and fun to eat as well.

Do you think that a chef’s joy in what they’re making transfers to the end product, when a stranger is tasting it?

Absolutely. As in all art.

I mean, there are the members of the “tortured artist” school, and they work their world, and they do it, and they can still come up with great things, but certainly if something is loved and enjoyed by the person who is making it – you know – I mean, when you see a great rock ‘n’ roll band play, they are having fun on stage because they’re doing what they’re supposed to do and they really dig it. Like, REM on tour is one of the greatest bands you’ll ever see ’cause they’re great at it, and they know what they’re doing, and they have a blast and it’s that same way in food.

Comedians are often expected to be “funny” on command. Do you find yourself being “volunteered” to cook? Do you mind?

No, I’ll happily – at the drop of a hat, I’ll cook any time, all the time. Being funny’s a little different because you have to have an intellectual component to it. You could cook silently, and still make delicious food, even if you were not necessarily in the mood. The techniques of the purchase, and then the actual heat transfer is something I enjoy all the time.

That said, being funny’s a little harder.

True confessions time: Do you ever resort to having Chinese food delivered in a plain brown bag, after midnight?

Of course I do. My kids love delivery Chinese food. I wouldn’t want to cut them out of an essential part of New York Culture. I believe they had Chinese food here last night. (I wasn’t here, but I think they did, last night). It’s from the local Grand Szechuan. They make these soup dumplings that are to die for.

You have a wonderful television presence, but you don’t fit the conventional “handsome actor” television host model. How did someone like you become one of the coolest chefs on TV?

You know what? Being in front of a camera for a long time only makes you more like what you are naturally. You can’t really practice to become relaxed, it just eventually happens to you, but I think that my reliance on the traditions of the Italian table and the obviousness of it being merely my interpretation gave me a certain platform or a soapbox to talk from, and in the end, I didn’t really have to invent a character. I really just interpreted the great things about the food that I love. And that, I believe, is what makes it evident.

It doesn’t look like I’m trying to be a performer. I’m just doing what I do. And in that way, there’s no kind of strange colored glass that everyone looks at you through because you’re trying to do something that maybe is like trying to memorize someone else’s play, which is what actors do all the time.

I could never do that. I could never remember lines. But if you can give me the idea, I can kind of espouse what that is, and that’s really what I’ve done. I’ve taken really good Italian cooking and just kind of shown people where and how it came from. And my reliance during a show, if I ran out of things to kind of show you, I just talked about the history, which I already knew because I pay attention. I’m a student of that game.

In your career, you’ve been involved with the design of a specific kind of rolling pin. Is there any kitchen gadget that you’d love to re-engineer, or any that you think should be eliminated?

You know, tools are something that are very personal. There’s things in each one that I find I’m very excited about but there’s nothing I would say should be absolutely removed except for the syringe. I don’t think anyone needs a syringe. But that’s – you know – if you need to marinate your turkey and you want to do it that way then you’re going to put it in there, but other than that, I think that all tools are very personal, and once you discover a way to do it, everyone should use whatever they’re comfortable with. There should be no dogma.

Do you have a favorite tool that you use? Are you a knife guy or is it the wooden spoon for you?

I like… you know my favorite tool is, I have this – in my kitchen there’s a giant (well, not giant, it’s probably ten feet by four feet). It is a marble slab. We do our – we live our entire lives on top of this piece of marble. We do homework there, we make pasta there, we roll out dough, we – tonight, for example, there’s a bake sale. My kids are doing a bake sale tomorrow for something called the Imagination Campaign, and everything we’re gonna do from now – they’re just walking in right now, from school – until everyone goes to bed, we will live our lives on our marble counter.

Connect with Mario

Follow Mario Batali on Twitter (@MarioBatali) and check him out on Eataly NYC‘s #TakingRequests.

About the author: Melissa A. Bartell

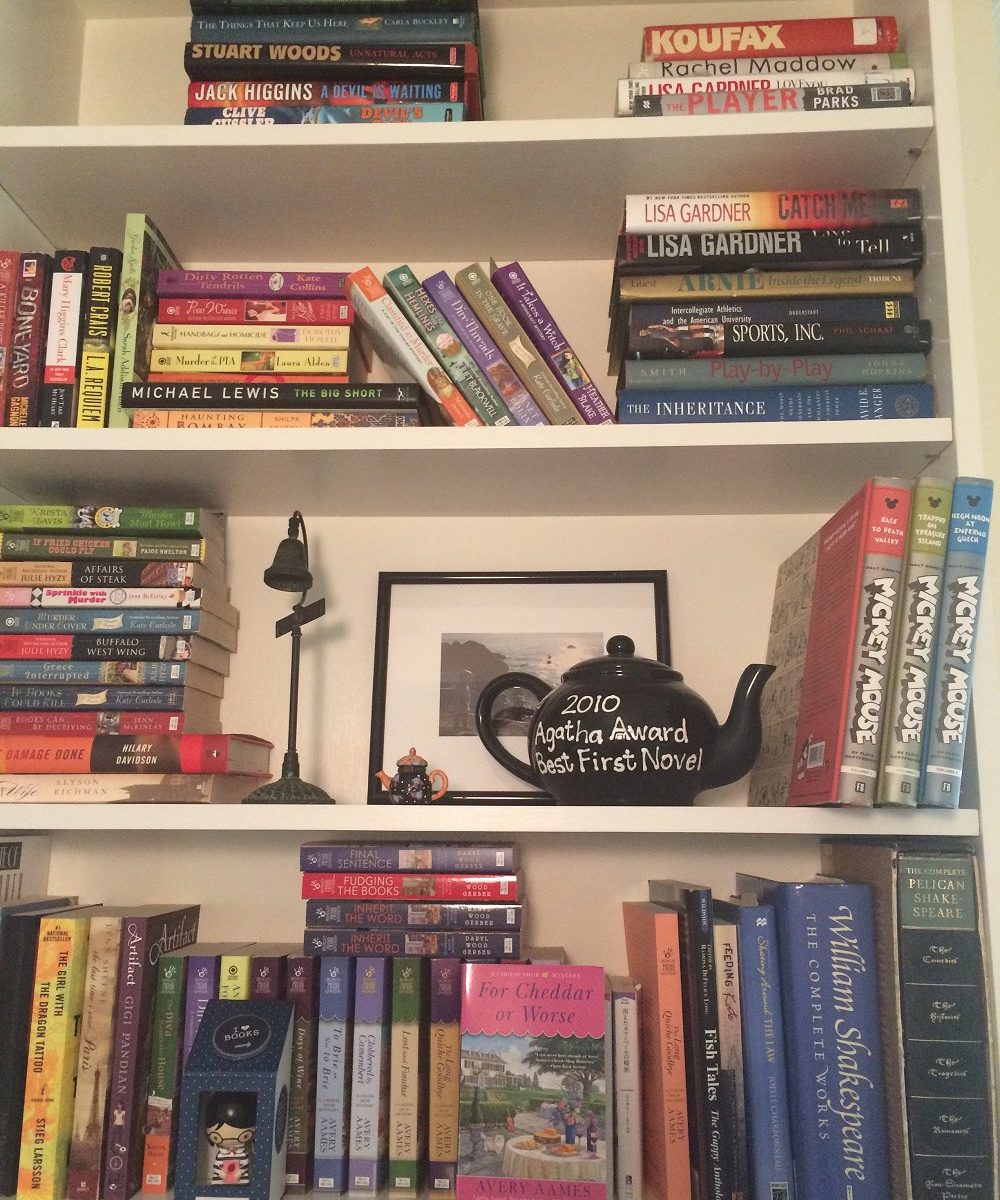

Melissa is a writer, voice actor, podcaster, itinerant musician, voracious reader, and collector of hats and rescue dogs. She is the author of The Bathtub Mermaid: Tales from the Holiday Tub. You can learn more about her on her blog, or connect with her on on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

Melissa is a writer, voice actor, podcaster, itinerant musician, voracious reader, and collector of hats and rescue dogs. She is the author of The Bathtub Mermaid: Tales from the Holiday Tub. You can learn more about her on her blog, or connect with her on on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

Color Me Murder is the first book in a new series for you. They say it takes a village to raise a child, but it seems it also takes a village of characters to create a book (and series). How do you go about creating your main character – choosing their names, traits, personalities? And all the supporting cast? Do you include traits of YOU and folks you know in them?

Color Me Murder is the first book in a new series for you. They say it takes a village to raise a child, but it seems it also takes a village of characters to create a book (and series). How do you go about creating your main character – choosing their names, traits, personalities? And all the supporting cast? Do you include traits of YOU and folks you know in them? Of course, we can’t forget all the animal characters in each of your series. Why do you include pets and how to you write them so delightfully?

Of course, we can’t forget all the animal characters in each of your series. Why do you include pets and how to you write them so delightfully? don’t do that, either. We see things differently depending on what we’ve been through in our lives.

don’t do that, either. We see things differently depending on what we’ve been through in our lives. New York Times Bestselling author Krista Davis writes the Paws and Claws Mysteries set on fictional Wagtail Mountain, a resort where people vacation with their pets. Her 1st Pen & Ink Mystery: Color Me Murder debuts February 27th. Don’t forget about her 5th Paws and Claws Mystery is NOT A CREATURE WAS PURRING, which came out earlier this month. Like her characters, Krista has a soft spot for cats, dogs, and sweets. She lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia with two dogs and two cats.

New York Times Bestselling author Krista Davis writes the Paws and Claws Mysteries set on fictional Wagtail Mountain, a resort where people vacation with their pets. Her 1st Pen & Ink Mystery: Color Me Murder debuts February 27th. Don’t forget about her 5th Paws and Claws Mystery is NOT A CREATURE WAS PURRING, which came out earlier this month. Like her characters, Krista has a soft spot for cats, dogs, and sweets. She lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia with two dogs and two cats.

insatiable desire for the truth. Can Jenna solve the murder without becoming a victim herself?

insatiable desire for the truth. Can Jenna solve the murder without becoming a victim herself? yourself into the world of Jenna and her friends after taking a break from working with that series?

yourself into the world of Jenna and her friends after taking a break from working with that series? come out this December? I said yes, so—wham—just like that, I have made my decision. Until June, that’s what I’m focusing on. Then I’ll go back to being flummoxed.

come out this December? I said yes, so—wham—just like that, I have made my decision. Until June, that’s what I’m focusing on. Then I’ll go back to being flummoxed. but I strive to do the best I can.

but I strive to do the best I can. I wish I’d known that outlining would help me. I only started that about seven years ago when I secured my first series.

I wish I’d known that outlining would help me. I only started that about seven years ago when I secured my first series. Agatha Award-winning Daryl Wood Gerber writes the brand new French Bistro Mysteries as well as the nationally bestselling Cookbook Nook Mysteries. As Avery Aames, she pens the popular Cheese Shop Mysteries.

Agatha Award-winning Daryl Wood Gerber writes the brand new French Bistro Mysteries as well as the nationally bestselling Cookbook Nook Mysteries. As Avery Aames, she pens the popular Cheese Shop Mysteries.

disciplined poet, but I find it a helpful format for times when other forms of writing fail me. Between Heaven and Earth came out last week and, so far, I’m most excited to hear that people who “don’t normally read poetry,” are finding it accessible and engaging.

disciplined poet, but I find it a helpful format for times when other forms of writing fail me. Between Heaven and Earth came out last week and, so far, I’m most excited to hear that people who “don’t normally read poetry,” are finding it accessible and engaging.

Kelly Chripczuk is a licensed pastor, Spiritual Director and writer who lives with her husband and four children in a 100+ year-old farm house in Central PA. She writes regularly online at

Kelly Chripczuk is a licensed pastor, Spiritual Director and writer who lives with her husband and four children in a 100+ year-old farm house in Central PA. She writes regularly online at

cup of chamomile tea and some shortbread, and of course, I’ll have enough to share.

cup of chamomile tea and some shortbread, and of course, I’ll have enough to share. underrepresented by publishers and publications or about the way racism lives in the city I know best, Charlottesville, Virginia, I want to always be trying to show people truth in a way that they can see it.

underrepresented by publishers and publications or about the way racism lives in the city I know best, Charlottesville, Virginia, I want to always be trying to show people truth in a way that they can see it. snippet: “Finishing and publishing a book is 20% talent and 80% discipline”. Do you agree? What is it that we all need to know about that double-edged sword called “discipline”?

snippet: “Finishing and publishing a book is 20% talent and 80% discipline”. Do you agree? What is it that we all need to know about that double-edged sword called “discipline”? What myths about being a writer (and the writing life) would you like to bust?

What myths about being a writer (and the writing life) would you like to bust?

Andi Cumbo-Floyd is a writer, editor, and farmer, who lives on 15 blissful acres at the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains with her husband, 6 goats, 4 dogs, 4 cats, and 22 chickens. Her books include Steele Secrets, Charlotte and the Twelve, The Slaves Have Names, and Writing Day In and Day Out. Her new book,

Andi Cumbo-Floyd is a writer, editor, and farmer, who lives on 15 blissful acres at the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains with her husband, 6 goats, 4 dogs, 4 cats, and 22 chickens. Her books include Steele Secrets, Charlotte and the Twelve, The Slaves Have Names, and Writing Day In and Day Out. Her new book,  At the moment I am in Vermont, so we would meet at Café Gatto Nero and I would enjoy a Mocha, perhaps iced.

At the moment I am in Vermont, so we would meet at Café Gatto Nero and I would enjoy a Mocha, perhaps iced. Ireland. What led to that decision?

Ireland. What led to that decision? rather I offer intuitive healing to include Reiki, guidance or medium readings, which allows for writing to be my primary focus.

rather I offer intuitive healing to include Reiki, guidance or medium readings, which allows for writing to be my primary focus. that’s first no matter where I am.

that’s first no matter where I am. Mary

Mary and/or snack were we to meet?

and/or snack were we to meet? Since Willa and Edith did a great deal of traveling, the possibilities for additional mysteries in the series are many.

Since Willa and Edith did a great deal of traveling, the possibilities for additional mysteries in the series are many. to invent?

to invent? meetings.

meetings. “What if ” take care of my own creation.

“What if ” take care of my own creation. into my other world and write.

into my other world and write. Sue

Sue

three-year hiatus in 2004, he hired nearly a dozen former employees within two months. My husband’s identity is fueled first and foremost by his role as a father, but as far as making his mark on the world, it was his career that steered the ship.

three-year hiatus in 2004, he hired nearly a dozen former employees within two months. My husband’s identity is fueled first and foremost by his role as a father, but as far as making his mark on the world, it was his career that steered the ship. Aside from travel and the occasional business dinner, when he came home at the end of the day, he was home. When we went on vacation, we were on vacation. He never brought his laptop to bed and he never spent a Saturday on a golf course with clients. So when someone proclaimed he would end up being bored without his work, we both laughed, knowing these comments were more likely a reflection of what the prospect of a life beyond work and career would mean for them rather than what was true for my husband.

Aside from travel and the occasional business dinner, when he came home at the end of the day, he was home. When we went on vacation, we were on vacation. He never brought his laptop to bed and he never spent a Saturday on a golf course with clients. So when someone proclaimed he would end up being bored without his work, we both laughed, knowing these comments were more likely a reflection of what the prospect of a life beyond work and career would mean for them rather than what was true for my husband.

cookbook while chatting with his best friend – a chef who helped ignite my husband’s passion for cooking.

cookbook while chatting with his best friend – a chef who helped ignite my husband’s passion for cooking.

Christine Mason Miller is an author and artist who just completed Moving Water, a memoir about the spiritual journey she’s taken with her family.

Christine Mason Miller is an author and artist who just completed Moving Water, a memoir about the spiritual journey she’s taken with her family.

Nourishment guide,

Nourishment guide,

Melissa is a writer, voice actor, podcaster, itinerant musician, voracious reader, and collector of hats and rescue dogs. She is the author of

Melissa is a writer, voice actor, podcaster, itinerant musician, voracious reader, and collector of hats and rescue dogs. She is the author of