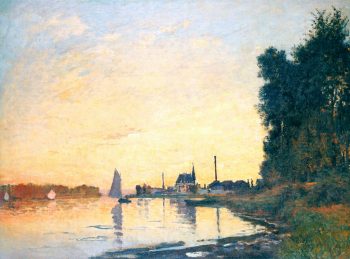

In 1871, the great Impressionist painter Claude Monet (1840-1926) left London where he had been living with his family during the Franco-Prussian war, and moved to Argenteuil, a suburb of Paris. Monet painted almost 200 paintings during the four years he lived in Argenteuil, often standing outdoors (or en plain air) to capture his impressions of life outside the hustle and bustle of the city. They were paintings that depicted family life – his young son Jean playing with a ball in the backyard of their home, his wife Camille peering out the front door expectantly waiting for him to arrive home from the train station after traveling to Paris for a meeting with his patron. They were painting of his friends, Renoir and Manet, who visited him with their own easels and palettes, the group of them painting together, each one recording their own impressions of the world around them. They were paintings of Argentueil itself – an idyllic harbor scene with the intruding pinnacle of industry as the factory smokestack becomes the focal point, drawing one’s eyes away from the blue water and white sails of the ships.

Earlier this month I attended a small and carefully curated exhibit of these paintings at our Detroit Institute of Arts. Aptly titled, Framing Life, the curator expertly chose the paintings from this period that demonstrated Monet’s ability to capture the beauty of family relationships, friendships, our natural surroundings, ordinary moments, and everyday objects and places.

Looking at these paintings, which were really just scenes from the artist’s daily life, I was reminded of the ways creative people try to capture the essence of our personal lives in our work. We want to cherish and keep this moments with us forever – the way the sun shines on the sidewalk where our child bounces a ball, the movement of white clouds across the azure blue of the sky, a friend smiling at us over the backyard fence, the trees laden with snow on a cold winter morning. We attempt to immortalize them in words, in melodies, in photographs, in soft water color “impressions” on canvas.

Monet, and his colleagues in the Impressionist School, were criticized by the art world for this focus on the everyday. Art was supposed to depict life at its largest – the lifestyles of the rich and famous, the lofty visages of royalty, the glory of battle. Instead of using art to illuminate mythological and Biblical themes, the Impressionists left their studios and went into the real world, literally by painting en plain air, and figuratively, with their subject matter.

But before long people began to appreciate the rebellious Impressionist artists for just these very reasons. “Ironically,” writes art historian Ann Dumas, “the Impressionists former status as renegades enhanced their appeal to the connoisseurship and speculative skills of the bourgeois collector…(it was) a new art for a new class that wanted images of the world they inhabited.”

Sometimes it’s difficult to make the real world beautiful, but the artist is compelled to try. When the wider world becomes too dark, we turn to the beauty of our own small worlds, cherishing and immortalizing that beauty with our words, our images, our impressions.

Framing Life. As I sit at my desk, looking out the window at the bare tree branches etched before me, I place a mental frame around this moment, this space. As I walk through the quiet streets of my little town, looking into shop windows, stopping for a coffee and the bookshop, smelling the scent of fresh bread oozing from the bakery, I place a mental frame around the sights and sounds. As I wake on a cold winter morning, my husband sleeping peacefully beside me, the promise of a new day ahead of us, I place a mental frame around that picture too.

That’s how I frame my life.

How do you frame yours?

About the Author: Becca Rowan

Becca Rowan lives in Northville, Michigan with her husband and their two dogs. She is the author of Life in General, and Life Goes On, collections of personal and inspirational essays about the ways women navigate the passage into midlife. She is also a musician, and performs as a pianist and as a member of Classical Bells, a professional handbell ensemble. If she’s not writing or playing music you’ll likely find her out walking or curled up on the couch reading with a cup of coffee (or glass of wine) close at hand. She loves to connect with readers at her blog, or on Facebook, Twitter, or Goodreads.

Becca Rowan lives in Northville, Michigan with her husband and their two dogs. She is the author of Life in General, and Life Goes On, collections of personal and inspirational essays about the ways women navigate the passage into midlife. She is also a musician, and performs as a pianist and as a member of Classical Bells, a professional handbell ensemble. If she’s not writing or playing music you’ll likely find her out walking or curled up on the couch reading with a cup of coffee (or glass of wine) close at hand. She loves to connect with readers at her blog, or on Facebook, Twitter, or Goodreads.

I think you framed like pretty darned well right here, Becca. I remember when I saw the Woman with the Parasol (there are two– I think it was this one but it might have been the other) in Musee d’Orsay — it was so big and beautiful that it took my breath away. I’ve wanted to see this exhibit (and hope it’s not too late,) I love how you were able to see beyond the beautiful paintings and into the life –theirs and yours. Lovely piece, Becca.

You are an artist too, you use words to paint the day to day experiences you encounter. When you share this way, you write in such us way that the words unite us in this human experience we call life. So grateful to have had the opportunity to work with you in the past. Your words speak volumes to me!