“In these relentlessly dark and riven times, I find myself beset by a near ravenous hunger for beauty.” ~Claire Messud

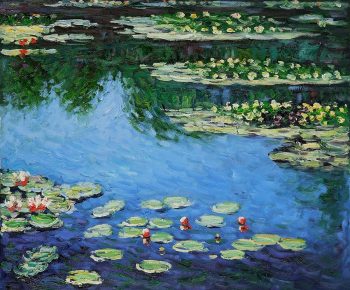

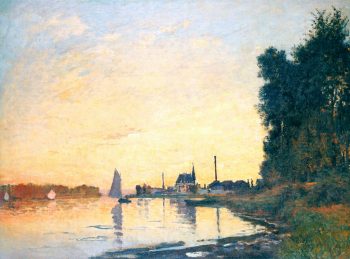

It happens when I hear the extraordinarily poignant melody of a Chopin Nocturne, when I gaze on the placid hues of a Monet watercolor, when I read the lines of a Mary Oliver poem. For those moments in time, my soul expands, my spirit quietens, my heart calms its racing, and I feel reassured.

It happens when I hear the extraordinarily poignant melody of a Chopin Nocturne, when I gaze on the placid hues of a Monet watercolor, when I read the lines of a Mary Oliver poem. For those moments in time, my soul expands, my spirit quietens, my heart calms its racing, and I feel reassured.

In our modern world it’s so easy to discount the importance of Art. There are such huge divisions among people, there is massive weaponry being tested and touted, there are innocent children being killed in school and separated from their families by virtue of nationality alone. We are taking sides against one another, brother against brother, mother against daughter, husband against wife. There is so much work to be done, even to begin the long process of bending history toward justice, as Martin Luther King promises us will occur.

What use is a song, a painting, a poem in the face of so much outrage? Who feels like dancing or singing anyway? Isn’t it just easier to go to work, do your job, come home and settle on the couch watching TV news or scrolling your Twitter feed for the latest outrage? Or try and escape from it all by numbing yourself with food or alcohol or other destructive behaviors?

We have been trained to believe that if something isn’t immediately useful and purposeful, its benefits cannot be measured, evaluated, calculated, and monetized, then it’s not worthy. It’s dispensable. We can get along without it. But if we accept this, I fear we risk losing sight of what makes us human.

I believe the quality of life is not measured by material goods or celebrity or social media status. It is a rich and sensitive mind, a giving heart, and meaningful human relationships that feed our souls and lead to the truest fulfillment we’ll find in this lifetime. Art is a bridge between the chaos of the modern world and the spiritual refreshment we so desperately need.

As difficult as it may be to scientifically analyze the benefits of art on a personal or societal level, there is no doubt in my mind that Art has the power to heal, to reframe thinking and to encourage justice. We learn compassion for others when their circumstances come alive in stories. We see the beauty of nature in paintings on canvas. We hear emotion come to life through music. We marvel at the fortitude these artists demonstrated, making art in the face of terrible trouble. Art lifts us up to possibility, to the creation of beauty within our own spheres. It encourages quiet and thoughtfulness. It makes us take stock and think.

Because truthfully, every nation at some time in its history has faced a reckoning similar to the one we’re facing now. Where will we stand – on the side of truth and honor and service? Or on the other side.

And what will we do with our anxious minds and spirits while we make that decision? We will illuminate and observe and perform. Our soul cries out for it, our hearts ache for it.

And what will we do with our anxious minds and spirits while we make that decision? We will illuminate and observe and perform. Our soul cries out for it, our hearts ache for it.

Novelist Claire Messud writes: “Art has the power to alter our interior selves, and in so doing to inspire, exhilarate, provoke, connect, and rouse us. As we are changed, our souls are awakened to possibility – immeasurable, yes, and potentially infinite.”

So go and make some Art. Create it or soak it up in silence. Lift your voice in song, spin your body in a dance. Awaken your soul to possibility, immeasurable and infinite.

You will be changed. And so will the world.

About the Author: Becca Rowan

Becca Rowan lives in Northville, Michigan with her husband and their Shih Tzu puppy Lacey Li. She is the author of Life in General, and Life Goes On, collections of personal and inspirational essays about the ways women navigate the passage into midlife. She is also a musician, and performs as a pianist and as a member of Classical Bells, a professional handbell ensemble. If she’s not writing or playing music you’ll likely find her playing with the puppy or curled up on the couch reading with a cup of coffee (or glass of wine) close at hand. She loves to connect with readers at her blog, or on Facebook, Twitter, or Goodreads.

Becca Rowan lives in Northville, Michigan with her husband and their Shih Tzu puppy Lacey Li. She is the author of Life in General, and Life Goes On, collections of personal and inspirational essays about the ways women navigate the passage into midlife. She is also a musician, and performs as a pianist and as a member of Classical Bells, a professional handbell ensemble. If she’s not writing or playing music you’ll likely find her playing with the puppy or curled up on the couch reading with a cup of coffee (or glass of wine) close at hand. She loves to connect with readers at her blog, or on Facebook, Twitter, or Goodreads.

This month I returned to the poetry of Jane Kenyon and Donald Hall, two poets who happen to be married to one another and who, for me at least, really embody this intersection of life and art. I return to Hall’s memoir,

This month I returned to the poetry of Jane Kenyon and Donald Hall, two poets who happen to be married to one another and who, for me at least, really embody this intersection of life and art. I return to Hall’s memoir,  There are those who will say that creative output is more perspiration than inspiration, that when you begin the work, the inspiration follows. “Inspiration usually comes during work, not before it,” wrote author Madeleine L’Engle.

There are those who will say that creative output is more perspiration than inspiration, that when you begin the work, the inspiration follows. “Inspiration usually comes during work, not before it,” wrote author Madeleine L’Engle.

I might finish one book and pick up another; my husband might move into the den and catch the latest replays from Saturdays soccer matches.

I might finish one book and pick up another; my husband might move into the den and catch the latest replays from Saturdays soccer matches. Of course comfort care for me is heavily weighted toward enjoying a creative life. It means books and music. It means enjoying lovely scented body creams and fresh home cooked food. It means a soft blanket to wrap around my shoulders on chilly mornings. It means looking for beautiful moments in the day – watching the sunrise from my favorite window, hearing a friend laugh, cuddling on the couch with my husband.

Of course comfort care for me is heavily weighted toward enjoying a creative life. It means books and music. It means enjoying lovely scented body creams and fresh home cooked food. It means a soft blanket to wrap around my shoulders on chilly mornings. It means looking for beautiful moments in the day – watching the sunrise from my favorite window, hearing a friend laugh, cuddling on the couch with my husband.

A few minutes later we ended our conversation feeling immensely better for having admitted that sometimes we’re not filled with sunshine and light, even though we might pretend to be. We’ve become conditioned to hide our darker emotions – grief, fear, loneliness, anger – because society seems to frown upon them. We’re encouraged to “look on the bright side,” or “find the silver lining.” Our spiritual friends will advise us to “give it all to a higher power” because “it’s in their control.”

A few minutes later we ended our conversation feeling immensely better for having admitted that sometimes we’re not filled with sunshine and light, even though we might pretend to be. We’ve become conditioned to hide our darker emotions – grief, fear, loneliness, anger – because society seems to frown upon them. We’re encouraged to “look on the bright side,” or “find the silver lining.” Our spiritual friends will advise us to “give it all to a higher power” because “it’s in their control.”

The book’s structure mirrors thought, so it feels as if we’re inside Shapiro’s head as her thoughts bounce back and forth between the present and various memories of her 17 year marriage to film-maker Michael Maren (whom she refers to only as M. throughout that book). She quotes from her own journals, the ones written on their honeymoon and in the early days of the marriage. She recalls events in their lives that illustrate the complexity and steadfastness of their relationship. She interjects pertinent quotes from writers and philosophers that illustrate her thinking, like this one from philosopher William James that stands alone in the middle of a page: “The constitutional disease from which I suffer is what the Germans call Zerrissenheit, or torn-to-pieces-hood. The days are broken in pure zig-zag and interruption.”

The book’s structure mirrors thought, so it feels as if we’re inside Shapiro’s head as her thoughts bounce back and forth between the present and various memories of her 17 year marriage to film-maker Michael Maren (whom she refers to only as M. throughout that book). She quotes from her own journals, the ones written on their honeymoon and in the early days of the marriage. She recalls events in their lives that illustrate the complexity and steadfastness of their relationship. She interjects pertinent quotes from writers and philosophers that illustrate her thinking, like this one from philosopher William James that stands alone in the middle of a page: “The constitutional disease from which I suffer is what the Germans call Zerrissenheit, or torn-to-pieces-hood. The days are broken in pure zig-zag and interruption.”