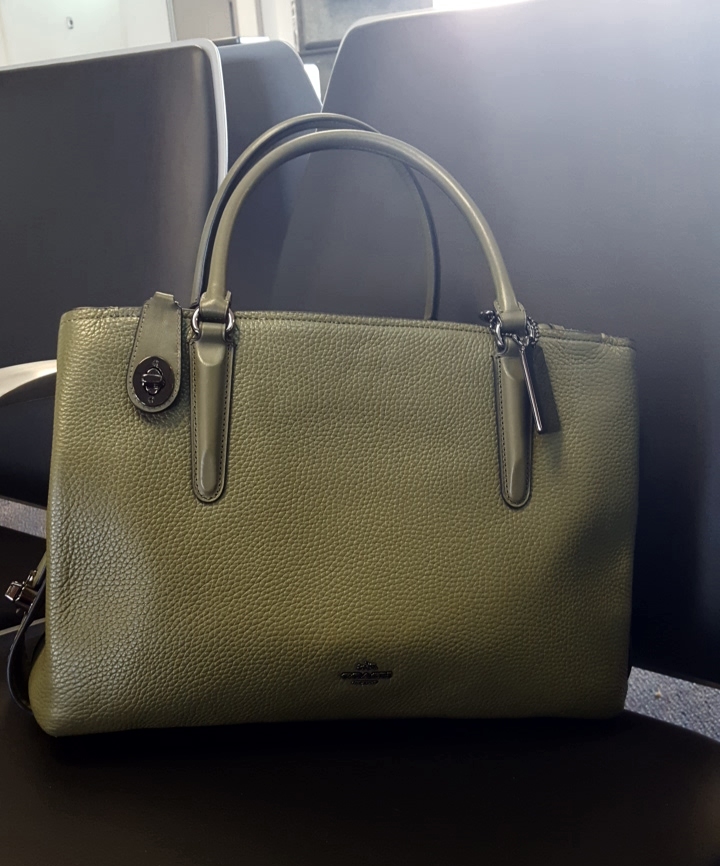

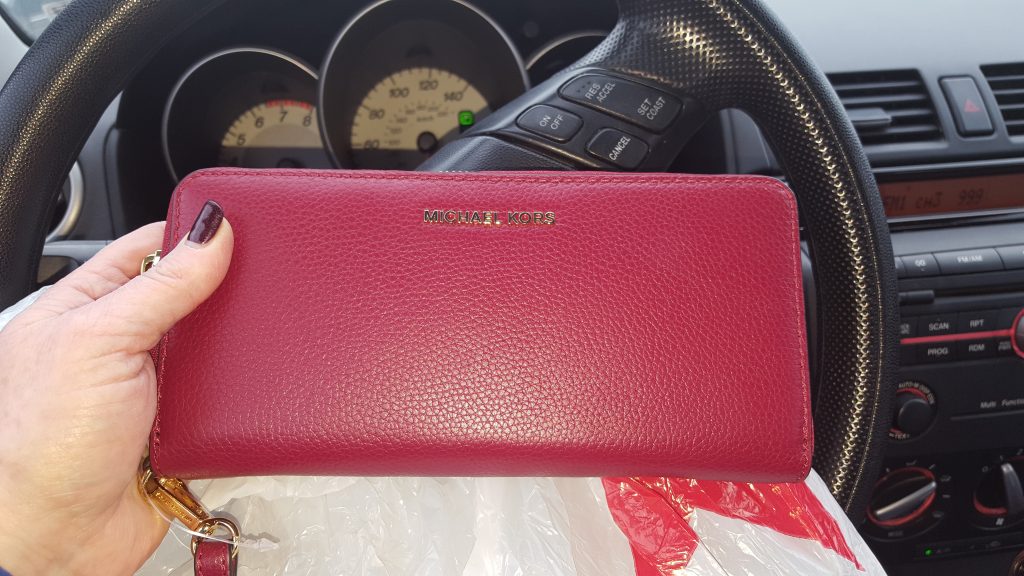

Many of the regular readers of Modern Creative Life have known me for more than a decade – from when when I first began writing my blog, or since the days when our predecessor, All Things Girl was still new. I’ve always written about my life in transparent ways. They’ve read about my life as a road warrior in the past, and my life of much less travel now. They know that I sometimes engage in retail therapy, and that I believe the first cup of coffee in the morning is more than just a warming brew; it’s a ritual. What they – and you – you might not know, though, is that I’m adopted.

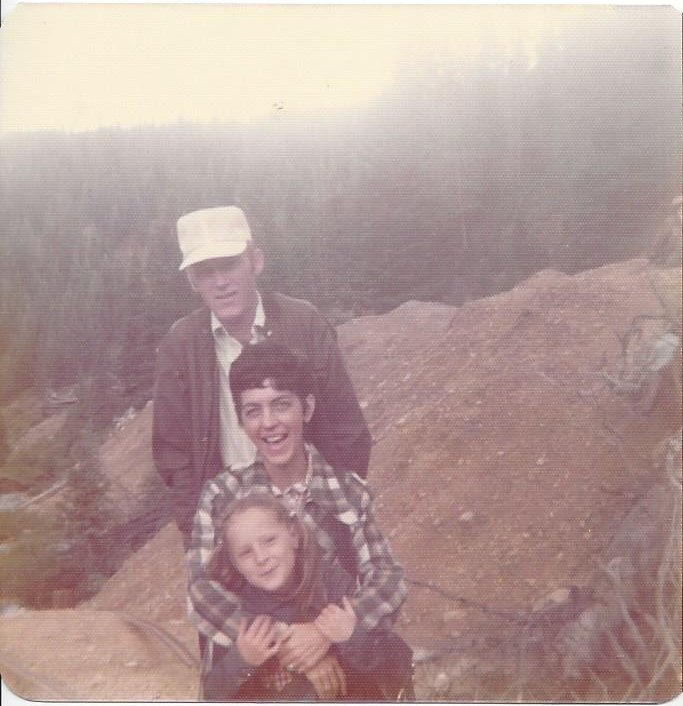

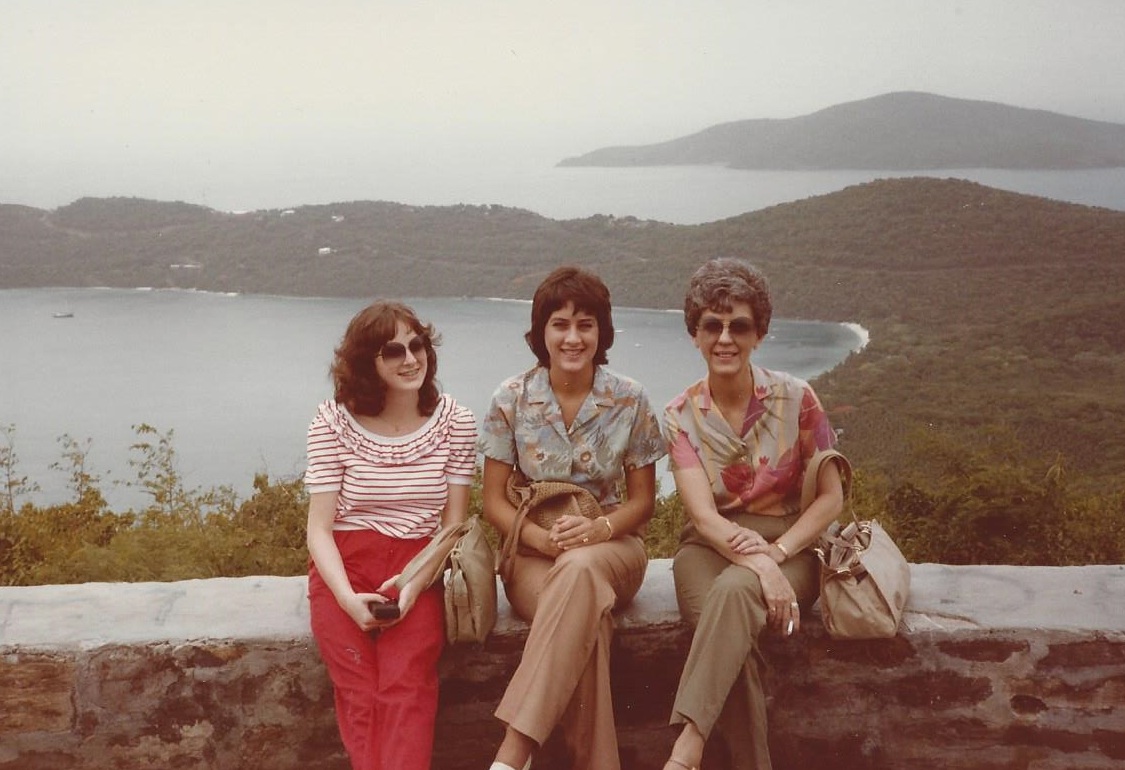

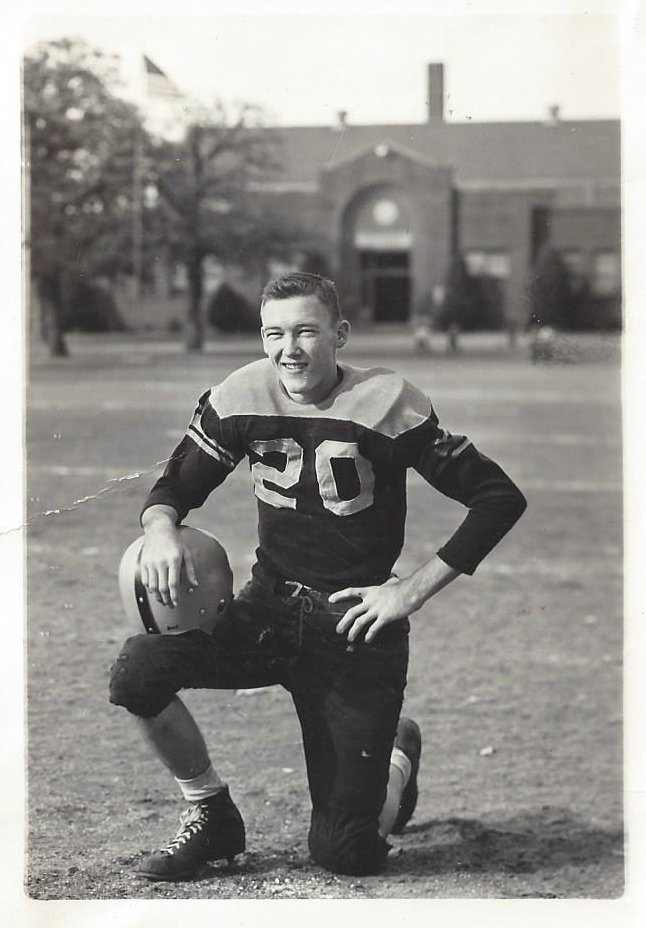

I have written about my mother, and I shared the challenges of grieving the loss of my daddy just this summer. The DNA of neither of these people runs through my veins. Yet, when I think of my parents, I think of Mary Beth and Tom.

Being adopted has always been simply a fact, like my hazel eyes and my love of books.

It was never a secret in our family. Our mother had been unable to carry a child to term and so the path to motherhood – the path to creating a family – was one that went through kind doctors, lawyers, and judges. The opportunity to nurture a child began with another woman, one who was selfless, giving up something precious in the hopes that this being growing inside her would have a life better than she was able to offer at that moment.

My sister and I each knew our “birth story”.

Arranged through the family doctor, my sister’s adoption took place in 1961. The doctor knew a young woman who found herself pregnant and was unable to keep the child. He had performed a hysterectomy on our mother and knew she wanted a child. And within hours of my sister being born, she was in the arms of our mother and father.

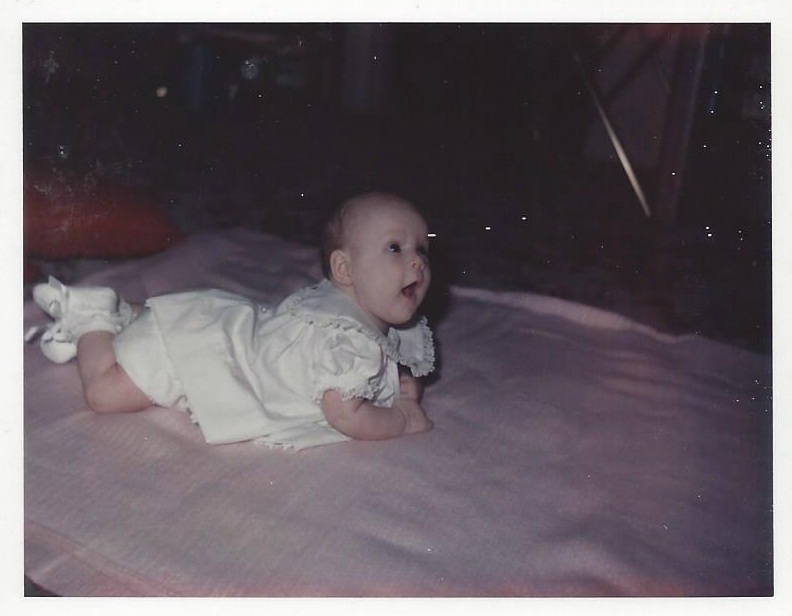

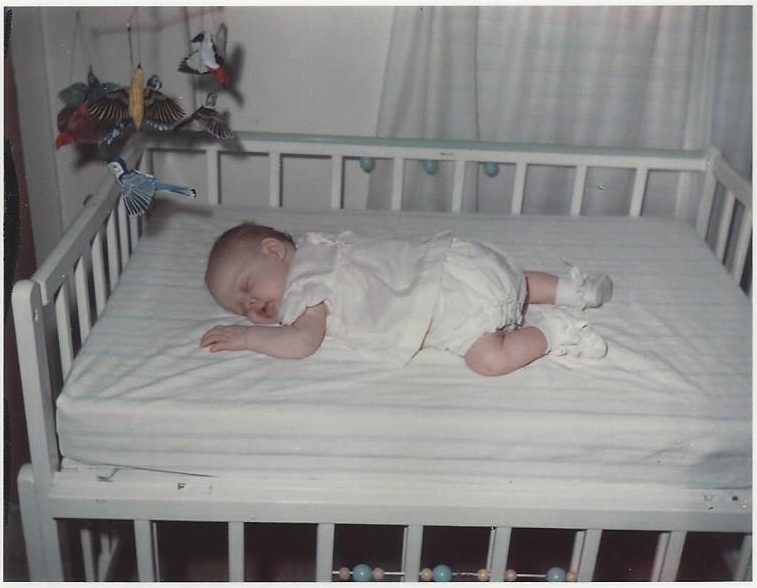

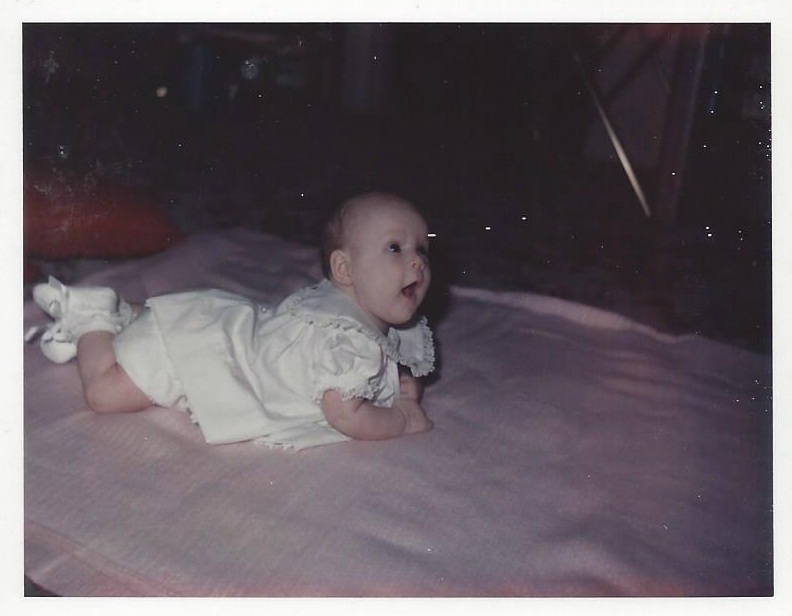

I came along seven years later. I was the child of a teenager who turned to a “home for unwed mothers.” My parents made an application and paid a deposit towards a baby the social workers found suitable for the family of three. Their only request was a child that was fair skinned, one that might resemble Daddy as my sister, Carol, had dark hair and an olive complexion like our mother. About a month after the approval of their application, they got a call that a fair-skinned red-headed little girl was available. I went home when I was two weeks old.

Of course, I’ve speculated about the young woman who had me while she was still, basically, a child herself. I was curious about that woman – courageous enough to care for herself and an unborn child, give birth, and then never know what happened after that moment.

I wondered about her, but I her identity wasn’t anything I dwelled upon.

I was never one of those adopted kids that believed finding my “real mom” was going to be the solution to any problem. It wasn’t going to make me “happy.” It wasn’t going to fix any current relationship. It was not the answer to rescuing me from any challenge.

Besides, I already had a “real mom.” A woman who ensured I got to school each morning and to ballet practice in the afternoons. The woman who slept in a chair in the hospital when I had my tonsils out and ferried me back and forth for every orthodontist appointment.

To be honest, my mother – my real mother, the woman who adopted me as a tiny babe, the one who ensured I had seasonally appropriate clothes, birthday parties, and a full tummy – was not perfect. I always suspected that she suffered from bi-polar disorder, noticeable mostly when she was in a depressive state, as those manic states were ones we could all swing with more easily.

In the South, especially in the days before social media, we called women who struggled with mental illness “delicate,” and just hoped for the best. We’ve come a long way in dealing with mental illness, but in those days, it was a shameful secret that caused family members to walk on eggshells sometimes.

From the outside, it sounds like something challenging and dire. For me, it was simply…life. A challenge, yes, to be raised by a woman who struggled with mental illness and an inability to truly love herself. But let’s get real, every family, no matter how picture perfect it might be, has some dysfunction.

At the core of who I am, I am a realist. I may have a creative spirit, but I am logical to a fault. I had a mother, I had a father. I had no need to seek out anyone who provided the seeds to create me, so to speak, and I continued in that vein for most of my life. When I was pregnant with my oldest child in 1991, my thoughts were about the growing little girl inside me. I don’t recall ever pondering the woman who had been in my same position back in 1967 and 1968.

My second pregnancy in 1995 was different, and for the first time in my twenty-seven years, I got curious enough to ask the state for any information they had on my birth parents. My second pregnancy presented a small number of health challenges – borderline gestational diabetes, high blood pressure, bed rest due to toxemia, a need for an early delivery. Still, I didn’t really want to know who my birth mother was by name, just who she was genetically. I got a packet of papers from the State of Texas with every identifying nugget literally cut out. It didn’t satisfy all my medical and health curiosities, but it was something. Eventually, it was filed away, and somehow, in the intervening years, lost.

After my mother died in 2010, my curiosity returned. By this point and time, I’d become a life coach, and had worked through a shit-ton of those “childhood issues” with professionals. I wrote to the State of Texas once again, and received a packet of papers. Once again, with all identifying information cut out. It didn’t matter that I was clearly an adult, and had lots of counseling to deal with the variety of issues we all deal with. The State of Texas deemed I had no right to my Original Birth Certificate.

Then on December 30 2014, I was sitting on the lanai of John’s sister’s home in Fort Meyers beach and read an article in the Wall Street Journal about DNA testing helping Adoptees find their birth families.

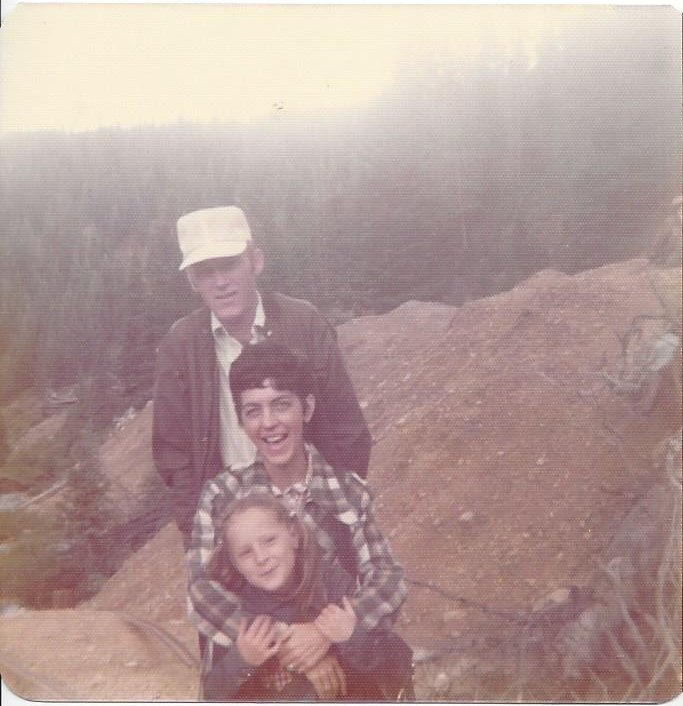

We’d gathered with the rest of John’s family to celebrate his mother’s 85th birthday. In the weeks leading up to that trip, we’d scanned all the family photos. In each, I saw the traces of all the men and women through the ages in each subsequent generation. All around the dinner table, on the beloved countenances of those ranging from four to eight-five, I saw how the shape of an ear or chin and hands and mannerisms brought these people together. It was a living example of the age-old nurture VS nature debate. DNA doesn’t lie when it comes to innate talents and physical traits.

I ordered the DNA Kits from both Ancestry.Com and 23andMe.Com. I spit in tubes. Weeks later, I received reports telling me that my ancestors were mostly Irish and Welsh with a splash of Scandinavian and Eastern European. It gave me insight into some of those conflicts of my teenage years – the stoic German ancestry of my mother combined with my flair for a story thanks to the Irish in me. But while this ancestor information led occasionally to a 2nd or 3rd cousin, it didn’t yield much more. And in most ways, just the ancestry information explained enough to me.

This past spring, though, my sister decided she wanted to know Where She Came From. She did the DNA and found a genealogist search angel. In less than a week, this search angel identified both of her birth parents and days later, identified my birth mother. I filed the proper paperwork to receive my original birth certificate, still only available if you knew all the answers to each blank (including the exact way a birth parent’s information was spelled on the document).

At the same time I was filling out paperwork, I was also laughing with John: how typical of my lucky sister! I’d been seeking information on and off for more than a decade and in her first foray into research got the answers she sought.

Weeks shy of my forty-ninth birthday, I wrote a letter to a woman in California. I told her about my life, my children, how blessed I was. I included a copy of my “original birth certificate”. I included a self-addressed and stamped post card for her to drop in the mail in case she was not interested in any communication, as well as my email address in case she was.

I knew had zero right to expect anything from her. How unfair or selfish of me would it have been to hold out any expectation or make any demands? I didn’t need or expect anything from this woman who had given me the gift of life and a good family. I had no desire to upset the apple cart of her life. Who knew what secrets she still kept? Who knew if anyone beyond her own mother knew she had a baby in 1968 when she was seventeen?

I wasn’t seeking my mother, I had a mother. I didn’t need to speak with this woman for me to feel whole or solve any problems in my life. I am whole thanks to therapy and life coaches and good books. What I didn’t underestimate, though, was that maybe, just maybe, the knowledge that I was safe and happy, healthy and whole, would be healing for her. Secrets, no matter how ancient, can be destructive.

She sent me an email about a week later. We spoke on the phone and she told me that the dates lined up, but she wanted to be sure. Because on the day that I was born, there were other babies born, too. She ordered her own Ancestry DNA Kit.

She confessed that when she returned home from the hospital, no one ever spoke about her having a baby. Not her, not her mother or step-father. The belief of those managing the adoptions of little babies back in the fifties, sixties, and seventies was that a young woman should walk away from the experience and pretend it never happened. That this was the key to going on with their life, unblemished. That this was the key to the child they gave up having a full and healthy life.

“The best gift I could ever receive,” she told me, “was simply the knowledge that you had a good life. That’s what we were told, that the babies adopted would have a good life.”

And I DID have a good life. I never wondered where my next meal would come from. I never wanted for shelter or clothing or toys. I didn’t go to bed cold or hungry. I was healthy. I got a great education. I had nice clothes, sturdy shoes, and never lacked the care of a doctor or dentist.

I lived in a house with a big yard and experienced what it was to have unlimited access to books and a friend in my cat.

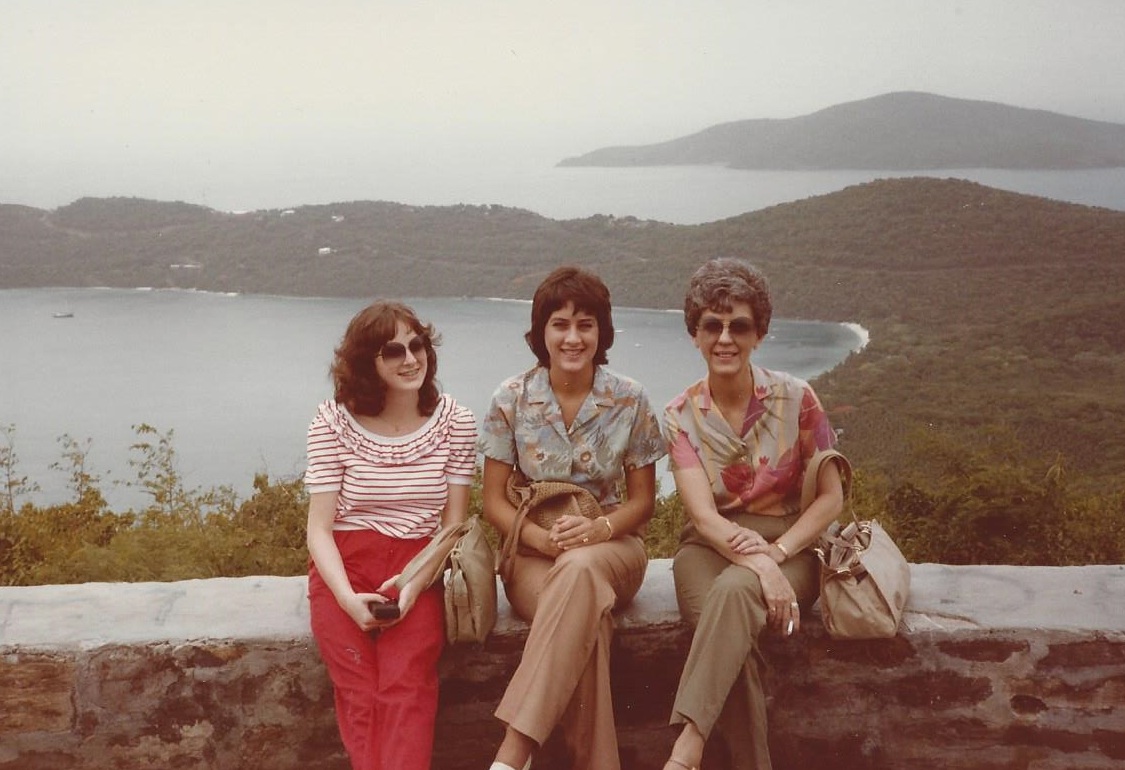

We went on nice vacations. I learned how to be a good member of society with added tutelage on societal norms such as how to behave in nice restaurants, how much to tip service folks, and how to be a good guest. (All activities not a normal in everyone’s life, something I discovered when a high school friend asked me where to put her purse at dinner on a date to Steak & Ale).

I was loved. Maybe not unconditionally by my mother because she couldn’t quite love herself. But I was loved and adored. And I certainly learned about unconditional love from my father. What I had, though, was a solid foundation of security and stability, the elements that Maslow identified as necessary for me to blossom into the curious and creative creature that I am.

The email confirming that this woman was the person who’d given birth to me arrived on the same day we buried my Daddy.

That was in summer. Now it’s December, and in a few short days, I will sit down at a table and see her face to face.

I will have the opportunity to see if I recognize myself in the arch of her eyebrow or the curve of her neck. I’ll be able to tell if she shares the shape of one of my daughters’ eyes, or if she gestures with her hands like any of us. I will no longer wonder whose fingers I have, or where my curvy figure came from.

We’ve been emailing once a week to share the highlights (and lowlights) of our daily lives. Threads of connection to see where our interests might cross or a turn of phrase feels familiar. We have no plans beyond getting together for an early dinner on my first night. I hope that that dinner leads to other visits while I’m in California, but I know that it might not.

And, of course, a part of me is wary. What if she doesn’t like me? I’ve never been the bubbly popular girl that other women love. My experience with John’s sisters, for example, remind me that sometimes, no matter how friendly and kind you are to others, they might not really like you, let alone seek you out to spend time with.

Deep within lies the hope that there’s a spark, a flash, some sort of intrinsic recognition, that connects us, bonds us, feels familiar. That something sustainable surfaces for the long haul.

I don’t need a mother, I had one. But I’ll never say that I don’t hope that I can create a relationship with this woman who gave birth to me. No, I don’t need her to be a mother. But it would be nice if she could be a friend.

About the Author: Debra Smouse

Debra Smouse is a self-admitted Tarnished Southern Belle, life coach, and author of Clearing Brain Clutter: Discovering Your Heart’s Desire and Clearing Soul Clutter: Creating Your Vision. When she’s not vacuuming her couch, you’ll find her reading or plotting when she can play her next round of golf. She’s the Editor in Chief here at Modern Creative Life. Connect with her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Debra Smouse is a self-admitted Tarnished Southern Belle, life coach, and author of Clearing Brain Clutter: Discovering Your Heart’s Desire and Clearing Soul Clutter: Creating Your Vision. When she’s not vacuuming her couch, you’ll find her reading or plotting when she can play her next round of golf. She’s the Editor in Chief here at Modern Creative Life. Connect with her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Poppins, The Jungle Book, and Winnie the Pooh. Long before the days of Cable TV, VHS, and The Internet, I watched black and white re-runs of Annette Funicello and the rest of the Mouseketeers. I danced around my room and sung along with every song, wishing for the moment I could be a Mouseketeer, too.

Poppins, The Jungle Book, and Winnie the Pooh. Long before the days of Cable TV, VHS, and The Internet, I watched black and white re-runs of Annette Funicello and the rest of the Mouseketeers. I danced around my room and sung along with every song, wishing for the moment I could be a Mouseketeer, too.

Walt Disney’s biggest regret about Disneyland: folks could see the city. He wanted it to be a place where anyone visiting could escape the real world and enter a world of dreams and imagination. So, when they began building Disney World in Florida, Walt was determined that anyone arriving in the Magic Kingdom, would have journeyed into a space and time where the outside world was completely unseen.

Walt Disney’s biggest regret about Disneyland: folks could see the city. He wanted it to be a place where anyone visiting could escape the real world and enter a world of dreams and imagination. So, when they began building Disney World in Florida, Walt was determined that anyone arriving in the Magic Kingdom, would have journeyed into a space and time where the outside world was completely unseen.

Debra Smouse is a self-admitted Tarnished Southern Belle, life coach, and author of Clearing Brain Clutter: Discovering Your Heart’s Desire and Clearing Soul Clutter: Creating Your Vision. When she’s not vacuuming her couch, you’ll find her reading or plotting when she can play her next round of golf. She’s the Editor in Chief here at Modern Creative Life. Connect with her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Debra Smouse is a self-admitted Tarnished Southern Belle, life coach, and author of Clearing Brain Clutter: Discovering Your Heart’s Desire and Clearing Soul Clutter: Creating Your Vision. When she’s not vacuuming her couch, you’ll find her reading or plotting when she can play her next round of golf. She’s the Editor in Chief here at Modern Creative Life. Connect with her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

manage grief differently.

manage grief differently.

the brilliant mums, the cheery pumpkins placed on porches. I am buying

the brilliant mums, the cheery pumpkins placed on porches. I am buying

At not-quite-fifty, I’m a little old to take on the orphan moniker, yet with the loss of my father last month, there is no one around who sat with me when I had the chicken pox at six months, slept in my hospital room when I was five and had my tonsils removed, or went to the ER with me when I fell off a chair and broke my arm when I was in the second grade.

At not-quite-fifty, I’m a little old to take on the orphan moniker, yet with the loss of my father last month, there is no one around who sat with me when I had the chicken pox at six months, slept in my hospital room when I was five and had my tonsils removed, or went to the ER with me when I fell off a chair and broke my arm when I was in the second grade. sounded strong and praised the surprisingly tasty hospital food and bemoaned his inability to watch the Western Channel in the hospital.

sounded strong and praised the surprisingly tasty hospital food and bemoaned his inability to watch the Western Channel in the hospital. Tupperware cabinet.

Tupperware cabinet.

a nod of the head to let us know that they get it.

a nod of the head to let us know that they get it. an artist. Her car is also filled with clothes and food and computers and cameras.

an artist. Her car is also filled with clothes and food and computers and cameras. the world and that safety comes from people we connect with, a favorite piece of equipment, and a port in the storm.

the world and that safety comes from people we connect with, a favorite piece of equipment, and a port in the storm.